The exit of former liberation leaders from power suggests that a new wind of change is blowing through Africa. Vusa Sibanda looks at a process that began with Kenneth Kaunda in 1991 and ended, at least for now, with Zuma this year

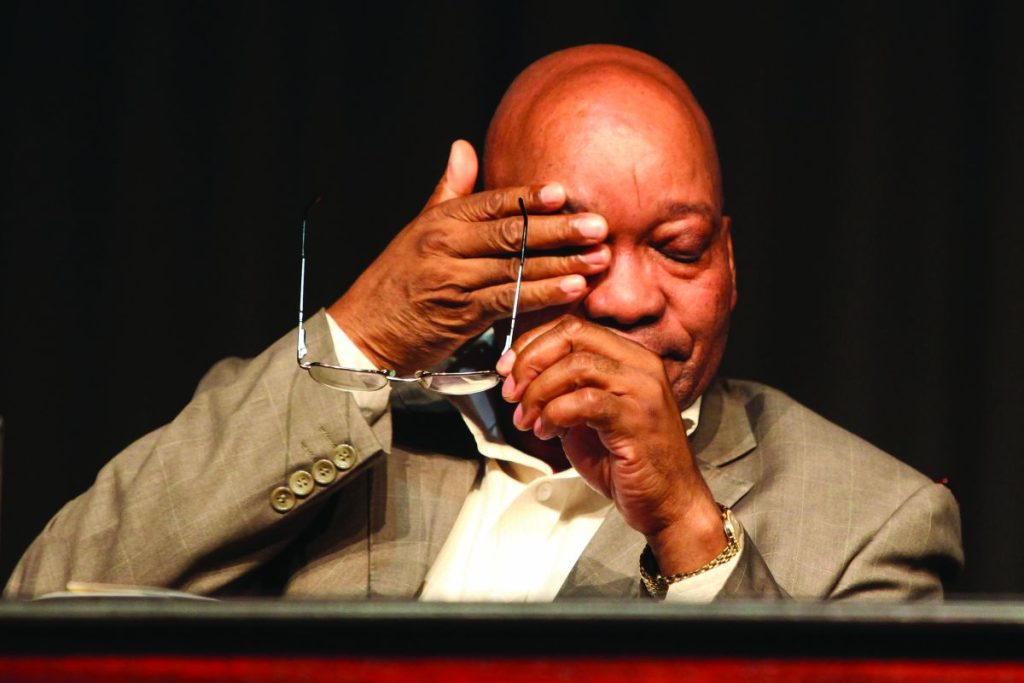

The resignation of South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma more than a month ago signals that the era of liberation fighter leaders in Southern Africa is coming to an end. In less than a year, Southern Africa has seen the exit of three such leaders in seemingly different circumstances, but apparently all bowing down to pressure. In August last year, Angola’s Eduardo dos Santos stepped down after almost four decades presiding over the oil-rich nation. In November last year, his Zimbabwean counterpart, Robert Mugabe, was forced to step down after being in power since 1980. After more than 10 days of uncertainty in South Africa, Zuma told the nation in a televised address on February 14, he was going – but only after being pushed out by his own party. After being in power for nine years, Zuma finally bowed to the inevitable and resigned “with immediate effect”. True to the age old adage that he who rises by the sword shall fall by the sword, Zuma took the reins of the ANC in 2007 in a party putsch against ex-president Thabo Mbeki. He reportedly orchestrated the ANC’s recall of Mbeki on the grounds that he had distanced himself from the real issues that affected the people. But Zuma’s presidency was characterised by controversy right from the beginning. Before assuming office, he caused dismay by first being accused of rape in 2006 and, secondly, telling the court he had showered after having unprotected sex with his young HIV-positive accuser to avoid, he said, contracting the virus. The claim incensed safe-sex and women’s rights campaigners not only because he was vice-president, but also because he was head of the country’s Aids council at the time. Zuma was acquitted of the charges but thereafter was often mocked in newspaper cartoons that depicted him with a shower nozzle sprouting from his bald pate. At Mandela’s memorial service in 2013, he was loudly booed by ordinary South Africans in front of world leaders. He had also been caricatured for his polygamous lifestyle, which he defended as part of traditional Zulu culture. One daily newspaper ran a cynical headline in response saying, “It is Zuma Culture, not Zulu Culture.”

He fought against all the odds to succeed Mbeki as the president of Africa’s economic power house in 2009. He managed to achieve the prize despite allegations of his involvement in an arms scandal involving 783 payments in the 1990s. The charges were dropped in circumstances that remain controversial, with allegations of political intervention. Now that he has been dethroned, Zuma finds himself fighting a court order that could reinstate corruption charges. Scandal was never far away from the Zuma presidency, with the perception that he fostered a culture of government corruption. One of the biggest was Nkandlagate, in which he is alleged to have used millions of dollars in public funds for an upgrade to his private residence in his Kwazulu Natal homeland. Described as “security improvements’, included a swimming pool and amphitheatre. The public protector, an anti-corruption body, ruled in 2014 that $23m of state funds had been improperly spent. In 2016, Zuma agreed to pay back some of the money in the face of a stinging constitutional court rebuke. He has also been accused of corrupt dealings with the wealthy Gupta family, which relocated to South Africa from India in 1993, just as white minority rule was ending and the country was opening up to the rest of the world. Their company, Sahara Computers now has an annual turnover of about $22m and employs 10,000 people. As well as computers, they have interests in mining, air travel, energy, technology and media. Brothers Ajay, Atul and Rajesh (also known as Tony) Gupta met Zuma about 10 years ago and since then have been accused of wielding enormous political influence in South Africa, with critics alleging that it is trying to “capture the state’ to advance their business interests, with. Zuma allegedly granting them influence over his cabinet appointments. In an embarrassing episode, the former president was reportedly seen in one of the ‘holding rooms’ at the Guptas as they dictated some of the ministerial appointments. He was forced into a humiliating climbdown in 2015 after firing a respected finance minister, Pravin Gordhan, and appointing a man widely seen as a stooge. As the rand went into free fall, Zuma bowed to pressure and re-appointed Gordhan to the crucial post. But he fought on and finally got the finance minister of his choice in March 2017 after dismissing Gordhan in a midnight reshuffle. The nation was particularly alarmed by the growing influence of the Guptas when they landed at a military base near Johannesburg in 2013. The scandalous relationship also incensed ANC stalwarts. Days after Zuma’s resignation, elite corruption police arrested several people at the Gupta compound in Johannesburg, signalling that their days of influence were over. Corruption aside, Zuma is also accused of having led the country into a quagmire of low growth, huge debt and record unemployment. During his time in power, South Africa was rocked by increasing social unrest over the failure to provide housing and basic services to the poorest in society. A man of nine lives, Zuma managed to hold on to power longer than would normally be expected of an embattled leader, thanks to his unique political skills. Unlike his predecessor Mbeki who was recalled with ease over comparatively insignificant charges, Zuma managed to outwit his rivals despite the glaring allegations against him. Now aged 75, the former herd boy who joined the ANC in 1959 and became an active member of its armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe, saw clinging on the presidency as yet another battle. He had “a very strong appeal” to the working class and the poor, according to Sdumo Dlamini, head of the Confederation of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), an ANC ally. He is believed to have survived by building a network of loyal ANC lawmakers and officials, and by trading on the party’s legacy as the organisation that ended white-minority rule. Zuma’s one time loyal supporter, Julius Malema, once vowed he was ready to kill for Zuma. The former ANC Youth League president and now leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), Malema later turned his back on his role model. “How can you have a president who marries every week?” He once remarked in reference to the former president’s polygamous lifestyle. Born on April 12, 1942, in Nkandla, a rural hamlet in Kwa Zulu-Natal province, Zuma’s extraordinary life resonates with his loyal grassroots supporters. Jacob Gezeyihlekisa Zuma, popularly referred to as ‘JZ’, rose through the ranks of the then-banned ANC, serving a 10-year stint as an apartheid-era political prisoner on Robben Island along the way. He later became head of ANC intelligence and was appointed a member of the ANC national executive committee in 1977 while in exile in Mozambique. Following the end of the ban on the ANC in February 1990, Zuma was one of the first ANC leaders to return to South Africa to begin the process of negotiations

A proud traditionalist, he is married to four wives and has 20 children. Former African Union (AU) chairperson, Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, a medical doctor, is an ex-wife. He loves slick tailored suits as much as he does full leopard-pelt Zulu warrior gear, and was often seeing engaging in energetic ground-stomping tribal dances during ceremonies in his village. In the past, he relished leading supporters in the rousing and now banned anti-apartheid struggle song Umshini Wami (Bring Me My Machine Gun), which became his signature tune.

Hero

The teetotaller and non-smoker was said to have had no formal education. But he used oratory and demagoguery to make up for apparent intellectual depth. As criticism of him mounted, Zuma maintained a cheerful public facade, often chuckling when allegations against him were repeated. But he was significantly weakened as senior ANC figures began to criticise him in public. His proverbial nine lives finally ended when his party moved to replace him with his vice-president Cyril Ramaphosa, a lawyer and former trade unionist. Ramaphosa is not without controversy either having amassed a huge fortune thanks, his critics say, to the ANC’s black empowerment programme. In neighbouring Zimbabwe, Mugabe resigned in November last year as parliament was starting impeachment proceedings against him, so ending his 37-year rule that began with the optimism of independence but took the country to the brink of economic collapse. The 93-year-old head of states stepped down six days after the military took over the country and placed him under house arrest. His departure was celebrated by people from all walks of life who resented how Africa’s bread basket had been turned into basket case thanks to crippling western sanctions against the government. Mugabe’s downfall was sparked by his sacking of his lifelong confidante and vice-president Emmerson Mnangagwa. The initial military take over was led by defence forces commander General Constantino Chiwenga. Now vice-president, Chiwenga said he had intervened to save Mugabe from a “criminal” cabal. Mnangagwa was reinstated as leader of the ruling Zanu-PF and later sworn in as republican president. He had fled Zimbabwe in early November saying he feared for his life. As a former security chief he was accused of being instrumental in crushing dissent in the 1980s in the notorious Gukurahundi, an operation by the army’s North Korean Fifth Brigade that led to the death of at least 10,000 civilians in Matebeleland. Mnangagwa has denied the allegations.

“It would be unfortunate if Mnangagwa were to extend the same governance culture that Mugabe pursued over the past 37 years,” said Morgan Tsvangirai, a former prime minister and the country’s one-time main opposition leader. “But it’s possible. Birds of a feather flock together.”

Tsvangirai died from cancer last month, leaving a fractured opposition ahead of Zimbabwe’s elections in July, which Mnangagwa has pledged will be fair and peaceful. When Mugabe led the former Rhodesia into independence as Zimbabwe, much hope was invested in him. Praised as a revolutionary hero of the African liberation struggle who helped to free Zimbabwe from British imperialism and white minority rule, the former teacher had a clear vision for the new nation, which involved redistribution of both land and wealth. Although Mugabe had initially won praise for championing one of Africa’s best education systems and for holding out an olive branch to the white settlers, his leadership deteriorated as he became more autocratic and pursued damaging economic policies. Western nations were particularly alarmed by his seizure of white-owned farms in favour of landless black people in 2000. They responded by isolating Mugabe politically and economically. As economic conditions deteriorated, he resorted increasingly to state intimidation to stay in office. Mugabe had a history of out-manoeuvring his rivals, but his refusal to groom a clear successor triggered a bitter battle within the Zanu-PF. As he began to age, his much younger wife, Grace Mugabe, began openly jostling for the country’s top job, using a cable of younger generation politicians known as G40 to purge the party of rivals.

Warfare

Mnangagwa, a lawyer and war veteran who lived in Zambia during the country’s liberation struggle, had been at Mugabe’s side during the independence war of the 1970s. He acquired the nom de guerre ‘the Crocodile’ during guerrilla warfare, and in 1980 became the first state security minister of independent Zimbabwe. Opposition parties accused Mnangagwa, 75, of helping to rig Zimbabwe’s 2008 elections in Mugabe’s favour. Appointed vice-president in 2014, he enjoys support in the security services and among liberation war veterans. Before his sacking, he was locked in a succession struggle with Mugabe’s wife. Increasingly, western donors viewed Mnangagwa and his so called ‘Lacoste’ group, as people they could do business with in the hope of an orderly transition as Mugabe’s health deteriorated. Some critics have likened the transition from Mugabe to Mnangagwa as “old wine in new skin”. “The struggle in Zimbabwe needs phases,” said Wonder Guchu, a journalist for the Herald newspaper. “The army removed Mugabe. Now we need to remove Zanu-PF. One bridge at a time.”

Welshman Ncube, an opposition leader, added: “I suppose it’s relief and anxiety at the same time. Relief that the symbol and face of the ruin of our country is finally over, and anxiety that the people who are taking over were supporters of his ruinous 37-year rule.”

In Angola whose population remains largely impoverished despite the country’s vast oil and gas wealth, the resignation of President José Eduardo dos Santos ended in August last year. His four decades in power had almost turned the country into a dynasty. In a surprise turn of events, dos Santos stepped down to allow his minister of defence, Joao Lourenço, to contest the presidential election under the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). But his departure has been viewed in some quarters as merely being window dressing. He has stayed on as party leader to continue wielding his influence and, say his critics, to protect his ill-gotten wealth. The son of immigrants from Sao Tome and Principe, dos Santos joined the MPLA in 1958 at the tender age of 16. He later joined the party’s armed wing in the struggle to free the country from Portugal’s colonial rule. His political activities soon forced him into exile, first to the Republic of Congo and then to the former Soviet Union, where he studied oil engineering. In November 1975, Angola declared independence. Agostinho Neto, leader of the MPLA, became the country’s first president and dos Santos its first foreign minister. With the end of Portuguese rule, a new power struggle began – this time between MPLA and rival liberation movement Unita. Cold War dynamics played out in the African country, with Neto backed by Russia and Cuba – and Jonas Savimbi, the leader of Unita, supported by the US and apartheid South Africa. The country slipped into a bloody civil war that would last almost 30 years. Throughout, dos Santos continued to serve in government until taking over the presidency after Neto’s death in 1979. Dos Santos had been in power ever since, until in 2016 – after 37 years in office – he decided not to run for re-election. He left behind a mixed legacy: securing independence and peace, and boosting oil production and infrastructure. But he has been accused of corruptly amassing wealth and failing to help the millions of Angolans who still live in poverty. Angola’s new President, Lourenco, has re-ignited hope of a better future for the millions of disenchanted citizens. He has vowed to root out corruption and begun by dismantling the family dynasty created by his predecessor. He fired the entire board of Angola’s state oil company Sonangol, including its chair, Isabel dos Santos, dos Santos’ eldest daughter. He also rescinded the affiliation of his sons Welwistchea and José Paulino, with the television networks Channel 2 and TPA International respectively. Another of dos Santos’ nine children, José Filomeno, recently resigned from his position as manager of Angola’s $5bn sovereign wealth fund. Prior to Laurenco’s ascending to power, rumours were awash that dos Santos had hoped to hand over the reins of power to one of his children, one of whom, Isabel, is Africa’s first woman billionaire according to Forbes magazine. It was at this point that high-ranking people in the party put their foot down. Many political watchers held that dos Santos would not allow Lourenco a free hand in key governance areas, a perception that was largely sounded when the first post-dos Santos cabinet retained several ministers. Lourenco, a former general who spent several years in the political wilderness after prematurely angling for the top job in the 1990s, has however already proved that he will not be dos Santos’ stooge. He is set to replace him as MPLA leader in a move that will patently clip the long time ruler of his powers and influence. Dos Santos said in March that the party should wait until December or April 2019 before choosing a new leader to replace him. He handpicked Lourenco to succeed him when he stepped down but by holding on to his position as head of the party he created two centres of power in the oil-producing nation.

Kaunda

As he continued to stamp his authority, Lourenco has reportedly ordered the immediate closure of the Office for the Revitalisation and Execution of Institutional Communication and Marketing of Administration (Grecima), a propaganda outfit that served dos Santos well. Angolan media portal, Journal de Angola, reported that Lourenco issued the closure orders via a press release that relieved Grecima boss, Manuel Antonio Rabelais, of his post. A presidential decree also transferred Grecima operations to an office under the presidency’s communications unit. Lourenco, 63, convinced key regime players he was the right man to succeed Jose Eduardo dos Santos. It was something of a turnaround for a man whose ambition nearly ended his career in the 1990s when dos Santos hinted he might stand down. Lourenco failed to hide his desire to succeed him and dos Santos moved against him. Like the former president, Lourenco studied in the former Soviet Union, which trained a number of rising young African leaders during decolonisation. In 1984, he was appointed governor of the eastern province of Moxico, Angola’s largest, quickly rising through the MPLA hierarchy. The retired general was deputy speaker of the National Assembly until his appointment as defence minister in 2014, which apparently secured his position as dos Santos’ favoured successor. The recent departure of former nationalist leaders is a continuum of Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda and Namibia’s Sam Nujoma stepping down from power in 1991 and 2005 respectively. Kaunda was defeated in elections by former trade unionist Fredrick Chiluba of the Movement for Multi-party Democracy (MMD) following the re-introduction of multi-party politics. He had ruled the copper rich country for 27 years, during which he had banned opposition political parties “to ensure national unity”. He finally succumbed to pressure to allow the return of multipartyism. Widespread discontent among the citizenry coupled with the global wind of change evidently led to Kaunda’s fall from grace. Regionally, he was praised for having championed the liberation of many countries, including neighbouring Zimbabwe and Namibia. He was also acknowledged for his efforts to marshal the country’s development from scratch. Once the former Northern Rhodesia, Zambia was a Cinderella country in the federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland as the colonial powers prioritised development of Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. On the domestic front, he was criticised for channeling the country’s resources to the liberation struggle at the expense of citizens. He was also accused of presiding over a crumbling economy in which essential commodities had become scarce and public infrastructure deteriorated. Widely seen as autocratic, he presided over a system that glorified his rule to an extent in which his zealots coined the term “In heaven God, here Kaunda”. He harassed and jailed those that dared to challenge him and one of the first acts of his successor was to close a number of ‘safe houses’ in which Kaunda’s opponents had been detained without trial. True to the saying that time heals, his record has been sanitised by the passage of time. He is now viewed as the father of the nation who is regularly invited to grace many public functions in a symbolic gesture. In March 2005, Namibia entered a new era – one without Sam Nujoma at the helm. After 15 years in power, the white-bearded liberation war leader, affectionately known as “the old man”, handed over to his successor, Hifikepunye Pohamba. Pohamba, has since been succeeded by Hage Geingob, the country’s third post-independence president. At least Nujoma, 87, was bowing out gracefully due to his advancing years. He said he was doing so in the knowledge that the foundations for democracy and economic prosperity had been laid through the collective leadership of his colleagues in Swapo (South West African People’s Organisation), which he had led for more than four decades. A former railway worker, Nujoma became the head of Swapo in 1960 and led it in exile against South African rule before returning to the country in 1989 and winning elections by a landslide the following year.