The subject of the Oscar-nominated film Hotel Rwanda, Kagame-critic Paul Rusesabagina is currently on trial for terrorism in Kigali. But, as Andrea Dijkstra discovers, questions are being raised over his chances of receiving a fair trial, while the dubious means used to detain him have led to a diplomatic fallout with Europe and the US.

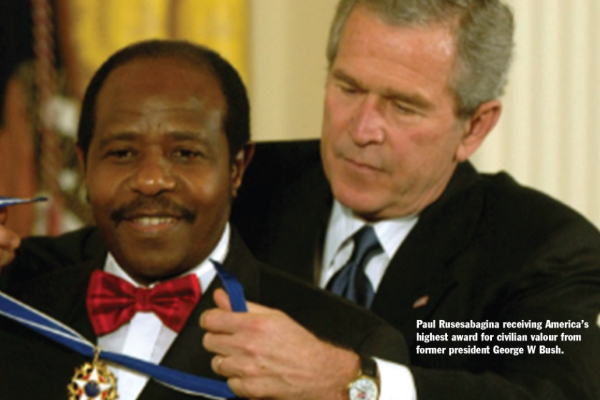

When Paul Rusesabagina boarded a flight from Chicago to Dubai on August 26, 2020, he never thought he would be setting foot on Rwandan soil only two days later. It had been more than 15 years since the 66-year-old former manager of Kigali’s Mille Collines hotel had accompanied the Irish film director Terry George to his homeland. That trip had led to George immortalising the Rwandan as a national hero for saving more than 1,200 people, who had taken shelter in his hotel during the 1994 genocide. The blockbuster, Hotel Rwanda, not only received three Oscar nominations, including one for Don Cheadle’s portrayal of Rusesabagina, but also turned the former hotelier into a minor celebrity. He attended film premiers and other star-studded events with UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador Angelina Jolie, and stood beside George Clooney and a Holocaust survivor at a 2006 rally in Washington to warn of a new genocide in Darfur in western Sudan. He started the Hotel Rwanda Rusesabagina Foundation and was honoured with dozens of awards, including the US Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honour in the United States, awarded by President George W Bush in 2005 for ‘remarkable courage and compassion in the face of genocidal terror’.

But in the years after Hollywood made him an international celebrity, a more complex image emerged of a fierce critic, who was using his celebrity to openly speak-out against Rwanda’s autocratic president Paul Kagame. While living in exile, first in Belgium and later in the US, he became politically active and co-founded the opposition party PDR-Ihumure, which became part of a coalition of opposition groups. The coalition has an armed wing, known as the National Liberation Forces (Forces de Libération Nationale or FLN), which has claimed responsibility for several attacks in Rwanda’s Southern Province since 2018. The Rwandan government has accused Rusesabagina of financially supporting the FLN and claims he was involved in the deadly attacks. Rusesabagina knew that returning to Kigali would be akin to a death sentence. After landing in Dubai in August last year, Rusesabagina boarded what he thought was a flight to Bujumbura, the largest city of Rwanda’s neighbour Burundi. He had an appointment with a Burundi-born pastor, Constantin Niyomwungere, who ran a dozen evangelical churches in Burundi, Rwanda, Belgium and elsewhere. According to Rusesabagina, the self-proclaimed ‘bishop’ had invited him to come and give speeches to several congregations in Burundi. The pair travelled back to Africa from Dubai in a private jet arranged by the cleric.

‘Inside the plane, I made sure that Rusesabagina couldn’t see the screen that displays the trip,’ the churchman later said. It was only when Rusesabagina stepped onto the tarmac in what he thought was Bujumbura, and was surrounded instead by Rwandan soldiers, that he realized he had been duped. Back in his homeland, he was promptly handcuffed and detained. His family only heard about his whereabouts when he was paraded in front of the media at the headquarters of the Rwanda Investigation Bureau in Kigali. While the Rwandan government recently admitted that it paid for the private jet that took Rusesabagina to Kigali, President Kagame claims that they didn’t violate any laws. He added: ‘There was no kidnap. There was no wrongdoing in the process of his getting here.’

Human rights organisations, members of the United States Congress, the European Parliament and Rusesabagina’s defence have described his rendition to Rwanda as illegal under international law. Fourteen US Senators and 23 US Congress members wrote a letter to Kagame in December requesting he return Rusesabagina, a Belgian citizen and US permanent resident, to the US to be reunited with his family.

‘Your government’s resort to the extrajudicial transfer of Mr Rusesabagina demonstrates a disregard for US law and suggests a lack of confidence in the credibility of the evidence against him,’ the senators and congress members stated.

‘This arrest is even illegal under Rwandan law, which prohibits so-called “deception”,’ Belgian emeritus professor of constitutional law and politics Filip Reyntjes told News Africa.

‘Such an illegal arrest automatically turns it also in an illegal detention.’

However, Reyntjes, who specialises in the African Great Lakes Region, doesn’t expect that Rusesabagina will be transferred to the US or Belgium, where he could continue his trial.

‘Belgium could send such a request, because Rusesabagina is a Belgian citizen, but I’m pretty sure that Rwanda will never cooperate,’ said the professor. The two countries have been involved in an ongoing diplomatic spat after Rwanda reprimanded Belgian Ambassador Benoît Ryelandt for interfering in the fate of Rusesabagina. The Rwandan Foreign Minister, Vincent Biruta, told the ambassador in March that Belgium’s behaviour ‘will determine the quality’ of future bilateral relations. Rusesabagina has been charged with nine offences, including terrorism, complicity in kidnap and murder, and forming a rebel group. If convicted, he could spend the rest of his life behind bars. Rwanda’s government cites a controversial video that Rusesabagina uploaded to You Tube in 2018 as ‘proof of his guilt’. In the video, the political exile stated in English that democratic change was no longer possible in Rwanda and he therefore pledged his ‘unreserved support’ to the FLN and called for armed resistance to the government. The statement shocked Rwanda, as the FLN had just carried out a violent attack in the town of Nyabimata in June 2018 in which three people were killed. Six months later, guerrillas ambushed three buses traveling through the nearby Nyungwe Forest, killing at least six and injuring dozens. In a September pre-trial hearing, Rusesabagina told the court he had contributed €20,000 (nearly $25,000) to the FLN. But he denied any wrongdoing. Prosecutors alleged that he also recruited dozens of fighters. From prison, Rusesabagina told the New York Times that his group’s role was not fighting, but ‘diplomacy’ to represent the millions of Rwandan refugees and exiles.

‘We are not a terrorist organisation,’ he said. In a brief courtroom appearance, Rusesabagina said the FLN had broken from its initial mission of defending civilians under threat from the Rwandan Patriotic Front. Insisting he had nothing to do with the attacks. He added: ‘I do not deny that the FLN committed crimes, but my role was diplomacy.’

Meanwhile, there has also been a lot of controversy and discussion about whether Rusesabagina had exaggerated his role in helping hotel refugees escape the 100-day genocide in 1994.

In recent years, some survivors declared that the hotel manager forced refugees to pay for their rooms and food.

‘I don’t believe much of these alternative narratives,’ Professor Reyntjes stated.

‘All of these negative stories only came up after Rusesabagina had started to become a critic of Rwanda’s regime. At the same time, being a hero obviously doesn’t justify committing crimes.’

Given the political nature of the charges, Rwanda watchers question the likelihood of Rusesabagina receiving a fair trial in Kigali. The outspoken critic has continuously been denied access to the legal counsel of his choosing. The international lawyers he has retained for his defence are still denied the necessary authorisations to represent him in Rwanda. His family is extremely worried about his medical condition. Rusesabagina is a cancer survivor and suffers from a cardiovascular disorder. Medication sent by his family was reportedly never administered to him. They also complain that Rusesabagina is being tried alongside 20 others, who have all pleaded guilty and incriminated him, and say he has not been given access to over 5,000 pages of documents in his case file. This led Rusesabagina to boycott his own hearings on the grounds he is unable to prepare his defence properly. Meanwhile in February, Al Jazeera broadcasted excerpts from a leaked phone call between Rwanda’s justice minister, Johnston Busingye, and two consultants from the British public relations firm Chelgate, in which Busingye admitted that Rwandan prison authorities have intercepted and read the correspondence between Rusesabagina and his Rwandan lawyers. The trial has also experienced several bizarre twists and turns. The pastor, who played a highly controversial role in the arrest of Rusesabagina, unexpectedly showed up at a hearing in March and gave a one-hour testimony, live broadcasted on You Tube, in which he incriminated Rusesabagina. He claimed, for example, that Rusesabagina intended to meet militant groups in Burundi. But the most surprising informant, unveiled during the trial in Kigali, wasn’t a Rwandan but was the American Michelle Martin, an assistant professor of social work at the California State University, who worked as a voluntary policy advisor with the Hotel Rwanda Rusesabagina Foundation during 2009 and 2010. The American academic revealed that she started taking screenshots of email correspondence by a member of Rusesabagina’s political outfit, detailing how charity funds, collected under the guise of helping widows and children in Rwanda, were used to fund armed groups intent on overthrowing the Rwandan government. In the lengthy testimony delivered in March, she even suggested that Rusesabagina made money transfers to people affiliated to the FDLR, the guerrilla movement created by the Hutu extremists who committed the 1994 genocide. But Kitty Kurth, spokeswoman for the dissolved foundation, told News Africa the claims were untrue. ‘We stopped talking to Martin because one day on the phone she was asking me odd leading questions including “why didn’t Paul join forces with the FDLR?”’

‘It kind of freaked me out. I explained that Paul was about creating a dialogue for Rwandans in the diaspora and the Great Lakes region and that he believes in the power of words.

‘The FDLR hated Paul, they called him a Tutsi-lover because he hired Tutsis at the hotel, was married to a Tutsi, his mother was a Tutsi and his two daughters are Tutsis.’

During her testimony, Martin presented herself as ‘an academic and researcher’ with a ‘natural curiosity’. She mentioned that she signed a contract with the Rwandan government for ‘scholarly work’. However, the witness failed to mentioned that she had been paid $5,000 a month for 12 months by the Rwandan government, despite declaring the payments on the US department of justice website where American citizens are required to register lobbying, carried out on behalf of foreign governments. The failure of the court to disclose this led David Himbara, a former member of Kagame’s staff and a current critic, to denounce the government as shameless. Writing in an opinion piece, he asked if they have ‘never heard of the term credible witness’, and denounced Professor Martin for having ‘zero credibility’. Meanwhile, Michela Wrong, a British journalist and Kagame critic, questioned why the state, which is ‘the world’s 11th poorest country and heavily dependent on Western aid’ was ‘willing to pay $5,000 a month to an informant’. Kagame, who helped end the genocide in 1994 and is widely credited with the development and stability Rwanda has experienced since, is also accused of intolerance of any opposition, whether domestic or international. Opposition parties and independent newspapers have been suppressed. Many Rwandans have fled the country, while many more have been scared into silence. The Rwandan security services have been accused of assassinating, abducting, attacking and threatening dozens of prominent Rwandans in Kenya, Uganda, South Africa, the UK and elsewhere. One of the most prominent cases was the killing of Patrick Karegeya, an outspoken critic and former spy chief, who was lured to a luxury hotel room in Johannesburg, South Africa, in January 2014 and strangled.

‘Any person still alive who may be plotting against Rwanda, whoever they are, will pay the price,’ Kagame said after the murder. Michela Wrong, who has just published the book Do Not Disturb, a critique of President Kagame’s autocratic style of rule, told News Africa that the international community ‘should be very worried whenever any state feels it has the right to reach half way across the world to harass, kidnap or kill critics in exile’. She said that Rwanda should transfer Rusesabagina to Belgium ‘where he can actually consult with lawyers, prepare his defence, and have a fair trial’. She added: ‘When Russia or Saudi Arabia mount these kind of operations, Western governments are quick to denounce their actions and repercussions swiftly follow.

‘Look at [former Russian military intelligence officer and double agent Sergei] Skripal, look at [murdered Saudi Arabian journalist and dissident Jamal] Khashoggi. But a different set of rules seems to apply when it comes to Rwanda, which continues to benefit from its status as a donor darling and treasured Western ally in Africa.’