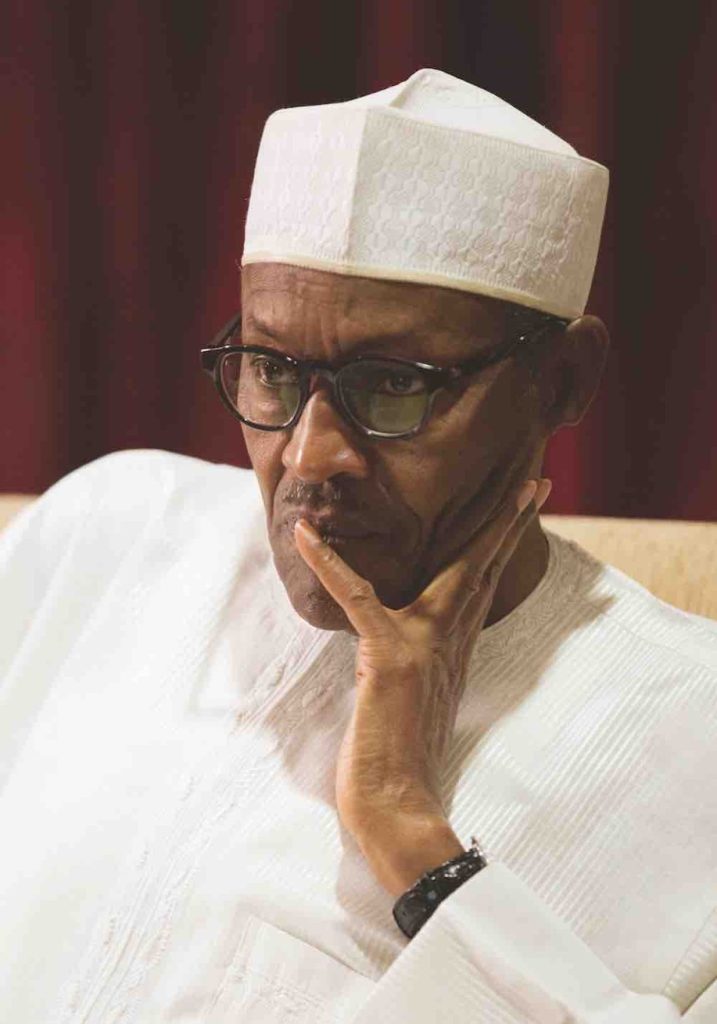

Vice-President of Nigeria, Yemi Osinbajo, reflects that the legacy of the Biafran War should be the quest for the country’s lasting unity

I was 10-years-old when my friend in primary school, Emeka, left school for good one day. He said his parents said they had to go back to East, war was about to start. I never saw Emeka again. My Auntie Bunmi was married to a gentleman from Enugu and I recall the evening when my parents tried to persuade her and her husband not to leave for the East. She did and we never saw her again. I recall distinctly how in 1967, passing in front of my home on Ikorodu road almost every hour were trucks carrying passengers and furniture in an endless stream heading east. Many Igbos who left various parts of Nigeria, left friends, families and businesses, schools and jobs. Like my friend and aunty some never returned. Many died. The reasons for this tragic separation of brothers and sisters were deep and profound. So much has been said and written already about the whys and wherefores that analyses will probably never end. This is why I would rather not spend this few minutes on whether there was or was not sufficient justification for secession and the war that followed. The issue is whether the terrible suffering, massive loss of lives, of hopes and fortunes of so many can ever be justified. As we reflect on this event today, we must ask ourselves the same question that many who have fought or been victims in civil wars, wars between brothers and sisters ask in moments of reflection: What if we had spent all the resources, time and sacrifice we put into the war, into trying to forge unity? What if we had decided not to seek to avenge a wrong done to us? What if we had chosen to overcome evil with good? The truth is that the spilling of blood in disputes is hardly ever worth the losses. Of the fallouts of bitter wars is the anger that can so easily be rekindled by those who for good or ill want to resuscitate the fire. Today some are suggesting that we must go back to the ethnic nationalities from which Nigeria was formed. They say that secession is the answer to the charges of marginalisation. They argue that separation from the Nigerian state will ultimately result in successful smaller states. They argue eloquently, I might add, that Nigeria is a colonial contraption that cannot endure. This is also the sum and substance of the agitation for Biafra. The campaign is often bitter and vitriolic, and has sometimes degenerated into fatal violence. Permit me to differ and to suggest that we’re greater together than apart. No country is perfect; around the world we have seen and continue to see expressions of intra-national discontent. Indeed, not many Nigerians seem to know that the oft-quoted line about Nigeria being a “mere geographical expression” originally applied to Italy. It was the German statesman Klemens von Metternich who dismissively summed up Italy as a mere geographical expression exactly a century before Nigeria came into being as a country. From Spain to Belgium to the UK and even the US, you will find many today who will venture to make similar arguments about their countries. But they have remained together. The truth is that many, if not most nations of the world, are made up of different peoples and cultures and beliefs and religions, who find themselves thrown together by circumstance. Nations are indeed made up of many nations. The most successful nations are those who do not fall into the lure of secession, but who through thick and thin forge unity in diversity. Nigeria is no different; we are, not three, but more like 300 or so ethnic groups within the same geographical space, presented with a great opportunity to combine all our strengths into a nation that is truly more than the sum of its parts. Let me say that there is a solid body of research that shows that groups that score high on diversity turn out to be more innovative than less diverse ones. There’s also research showing that companies that place a premium on creating diverse workplaces do better financially than those who do not. This applies to countries just as much as it does to companies. The US is a great example, bringing together an impressively diverse cast of people together to consistently accomplish world-conquering economic, military and scientific feats. It is possible in Nigeria as well. Instead of trying to flee into the lazy comfort of homogeneity every time we’re faced with the frustrations of living together, the more beneficial way for us individually and collectively is actually to apply the effort and the patience to understand one another and to progressively aspire to create one nation bound in freedom, in peace and in unity. That, in a sense, should be the Nigerian Dream – the enthusiasm to create a country that provides reasons for its citizens to believe in it, a country that does not discriminate or marginalise in any way. We are not there yet, but I believe we have a strong chance to advance in that direction. But that will not happen if we allow our frustrations and grievances to transmute into hatred. It will not happen if we see the media as platforms for the propagation of hateful and divisive rhetoric. No one stands to benefit from a stance like that; we will all emerge as losers. Clearly our strength is in our diversity, that we are greater together than apart. Imagine for a moment that an enterprising young man from Aba had to apply for a visa to travel to Kano to pursue his entrepreneurial dreams, or that a young woman from Abeokuta had to fill immigration forms and await a verdict in order to attend her best friend’s wedding in Umuahia. Nigeria would be a much less colourful, much less interesting space, were that the case. Our frustrations with some who speak a different dialect or belong to a different religion must not drive us to forget many of the same tribe and faith of our adversaries who have shown true affection for us. Let me make it clear that I fully believe that Nigerians should exercise to the fullest extent the right to discuss or debate the terms of our existence. Debate and disagreement are fundamental aspects of democracy. We recognise and acknowledge that necessity. And this event is along those lines – an opportunity not merely to commemorate the past, but also to dissect and debate it. Let’s ask ourselves tough questions about the path that has led us here, and how we might transform yesterday’s actions into tomorrow’s wisdom. Indeed our argument is not and will never be that we should ‘forget the past’, or ‘let bygones be bygones’, as some have suggested. Chinua Achebe repeatedly reminded us of the Igbo saying that a man who cannot tell where the rain began to beat him cannot know where he dried his body. If we lose the past, we will inevitably lose the opportunity to make the best of the present and the future. In an interview years ago, the late Dim Chukwuemeka Ojukwu, explaining why he didn’t think a second Biafran War should happen, said: “We should have learnt from that first one, otherwise the deaths would have been to no avail; it would all have been in vain.”

We should also be careful that we do not focus exclusively on the narratives of division, at the expense of the uplifting and inspiring ones. The same social media that has come under much censure for its propensity to propagate division, has also allowed multitudes of young Nigerians to see more of the sights and sounds of their country than ever before. And for every young Nigerian who sees the internet as an avenue for spewing ethnic hatred, there is another young Nigerian who is falling in love or doing business across ethnic and cultural lines; a young Nigerian who looks back on his or her NYSC [National Youth Service Corps] year in unfamiliar territory as one of the valued highlights of their lifetime. These stories need to be told as well. They are the stories that remind us that the journey to nationhood is not an event but a process, filled as with life itself with experiences some bitter, some sweet. The most remarkable attribute of that process is that a succeeding generation does not need to bear the prejudices and failures of the past. Every new generation can take a different and more ennobling route than its predecessors. But the greatest responsibility today lies on the leadership of our country. The promise of our constitution which we have sworn to uphold is that we would ensure a secure, and safe environment for our people to live, and work in peace, that we would provide just and fair institutions of justice. That we would not permit or encourage discrimination on the grounds of race, gender, beliefs or other parochial considerations. That we would build a nation where no one is oppressed and none is left behind. These are the standards to which we must hold our leadership. We must not permit our leaders the easy but dangerous rhetoric of blaming our social and economic conditions on our coming together. It is their duty to give us a vision a pathway to make our unity in diversity even more perfect.q

This is an edited version of the keynote address given by Yemi Osinbajo at the Yar’Adua Centre in Abuja in May on behalf of the Ford foundation and the Open Society initiative West Africa under the heading, ‘Memory and Nation Building – Biafra: 50 years after’